From Sight to Insight

Fei-Fei Li’s new book, ImageNet, and the beginnings of the deep learning revolution

The ability to perceive our surroundings encouraged us to develop a mechanism for integrating, analyzing, and ultimately making sense of that perception. And vision was, by far, its most vibrant constituent.

— Fei-Fei Li, The Worlds I See

The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI

Stanford computer science professor and AI pioneer Fei-Fei Li’s new book The Worlds I See is a personal memoir of growing up an aspiring scientist in a low-income, immigrant Chinese household as well as a first-hand account of the beginnings of the AI revolution. Li did her undergrad in physics at Princeton before deciding to focus jointly on computing and cognitive science for her PhD at Caltech. More specifically, Li was interested in the mechanism of vision.

One of her earliest experiments was actually a psychophysics study where she found that subjects are able to extract the gist of entire visual scenes after just milliseconds of exposure while their attentions were focused entirely on another task. The sheer speed and ease with which our brains our able to process visual cues completely underneath the hood of conscious thought is pretty incredible. Moreover, Li found that human visual perception is based on the recognition of things as part of well-defined categories (i.e. objects, people, places), as opposed to colors or textures or contours.

Inspired by this object-oriented theory of vision, in 2003, Li and her collaborators compiled the Caltech 101 dataset, comprised of over 9,000 images belonging to 101 different object categories. This made it the largest dataset at the time for machine learning. The performance gains on one-shot object categorization tasks trained on the dataset convinced Li of the power of bigger and more diverse datasets for improving models at a time when the field was primarily focused on improving algorithms.

ImageNet

Li is most known for her work on the ImageNet dataset and the corresponding ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). Completed in 2009, ImageNet is a database composed of 3.2 million images spread over more than 5,000 categories (Deng et al., 2009). The annual ILSVRC, which ran from 2010 to 2017, provided a standardized dataset and evaluation metrics for comparing different image classification models. Throughout the course of its run, the competition drove significant advancements in deep learning and CNNs for visual recognition tasks.

AlexNet and ResNet Break Barriers

A breakthrough occurred in 2012 when AlexNet, an eight-layer CNN submitted by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton, dramatically outperformed traditional computer vision models, achieving a top-5 error of 15.3 percent and beating out the runner-up by over 10 percent (Krizhevsky et al., 2012). AlexNet’s overwhelming success demonstrated the potential of deeper networks for improved performance and was one of the first models to leverage GPUs to accelerate training. These innovations led to a resurgence of interest in neural networks in the field and laid the groundwork for modern deep learning practices.

The fundamental CNN architecture that AlexNet was based on was introduced by Yann LeCun to recognize hand-written postal codes all the way back in 1989 (LeCun et al., 1989). However, despite the promise shown by CNNs, they remained largely underutilized in the broader field of computer vision for over two decades due to limitations in computational power and the lack of large-scale, labeled datasets required for training deep networks effectively. The paradigm shift that AlexNet induced owed largely to a perfect storm of the availability of big data through ImageNet and improvements in GPU computation. So, while AlexNet was an incredible breakthrough for deep learning, it was only possible because it stood on the shoulders of giants.

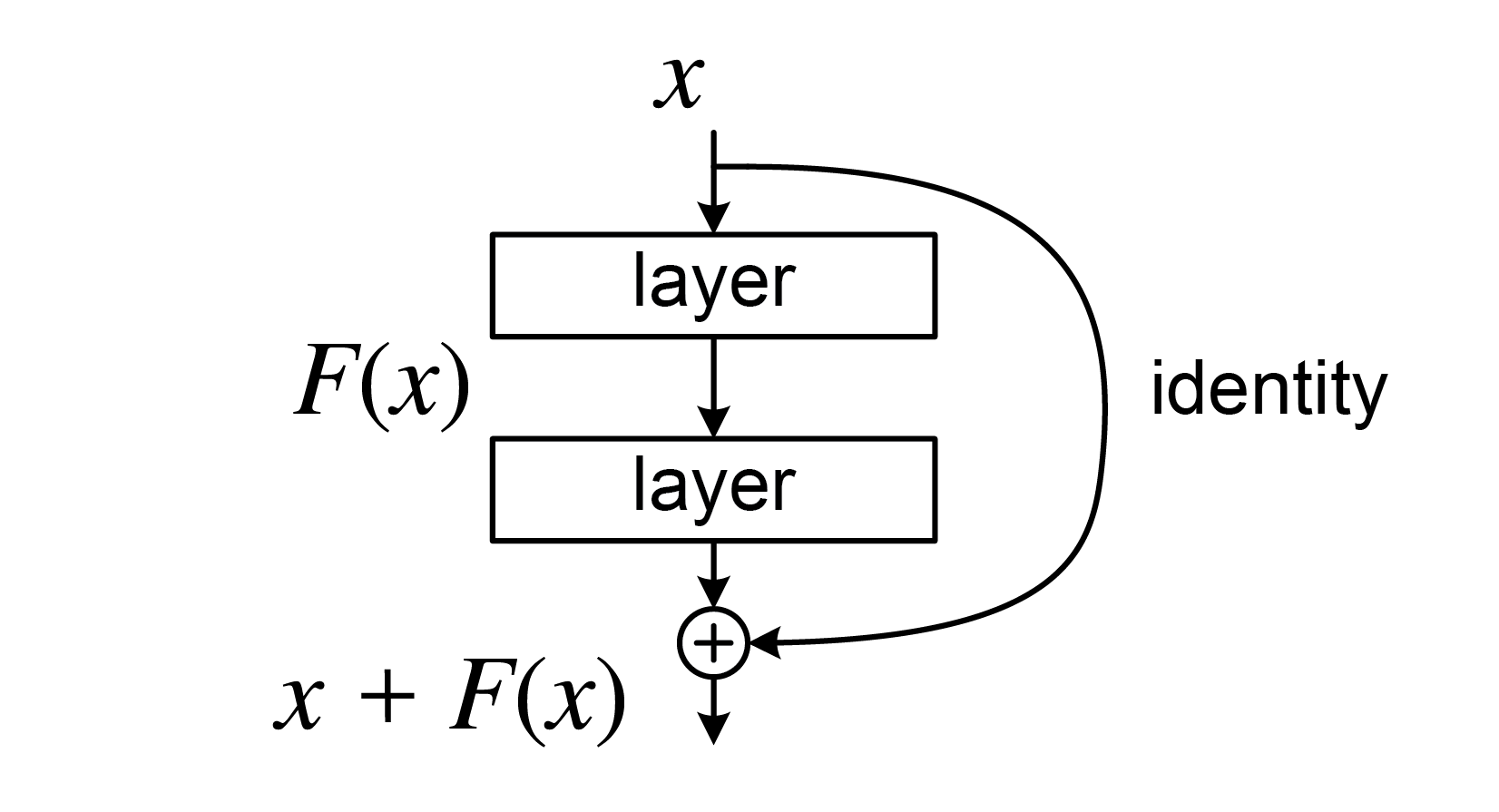

The next breakthrough of such magnitude was when ResNet, a residual neural network submitted to ILSVRC-2015, surpassed human-level recognition of ImageNet images with a test error of 3.57 percent (He et al., 2015). As researchers tried to train deeper and deeper models, they found that training error would actually start to increase. In theory, a deeper model with a training error no worse than a shallower model should be easy to construct: simply set the additional layers to identity mappings. However, the authors found that optimization methods were not able to find a solution at least as good as this identity-mapping solution. The ResNet paper introduced the concept of residual learning to address this degradation problem.

A residual learning block

Residual blocks consist of a stack of weight layers (two or three layers depending on the depth of the model) as well as a skip connection directly passing the input to the block to its output. Letting $H(x)$ be the underlying representation of this block, define the residual function to be learned as $F(x) := H(x)-x$. The overall output of the block is then given by $F(x) + x$. Now, it is very easy for the network to find the identity mapping by simply learning all the weights of $F(x)$ to be near zero. Stacking many of these residual blocks together forms a residual network.

The shallower ResNet-18 and ResNet-34 models use “Basic Blocks” which contain two 3x3 convolutional layers spanned by a skip connection. The deeper ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and ResNet-152 models use “Bottleneck Blocks” which contain 1x1, 3x3, and 1x1 convolutional layers, with a skip connection spanning all three layers. The 1x1 convolutions reduce and then increase dimensions such that the 3x3 convolution has smaller input and output dimensions, reducing time complexity and model size.

This skip connection method reminds me a lot of how some shortest path problems can be solved using a graph representation that involve additional edges which skip certain nodes (depending on the problem constraints) and may or may not be used as part of an optimal solution. Might be interesting to explore applications of graph theory to neural network design in a future post!

Some Philosophical Mumbo Jumbo

One major inspiration Li cites for her line of work actually stems from evolutionary biology, in particular one theory for the cause of the Cambrian explosion. The theory posits that, back when we were all microbes in the primordial soup, there was no need for intelligence because there was no way for us to sense outside stimuli to react to. Then, photosensitivity evolved. Suddenly, for the first time, organisms were awakened to a world outside themselves. Those that leveraged this newfound power to gain an evolutionary edge—navigating toward food or away from predators—survived to pass on their abilities. As photosensitivity matured into vision and other senses began to evolve, a central unit for processing this plethora of new data from the outside world became necessary. Ergo, the brain.

In other words, perception gave rise to intelligence, and sight became insight (Li, 2024). For me, framing the study of computer vision, as well as sensing and planning in robotics, as evolution-inspired approaches to coaxing out intelligence from effective perception is so incredibly compelling and fascinating.